“Establish an operational incident-handling capability for organizational systems that includes preparation, detection, analysis, containment, recovery, and user response activities.” — NIST SP 800-171 Rev. 2, 3.6.1

When a cybersecurity incident happens, the worst time to decide who’s in charge is during the incident.

Control 3.6.1 requires every organization to establish an operational incident-handling capability — not just a policy, but a real, functional process for managing and responding to security events.

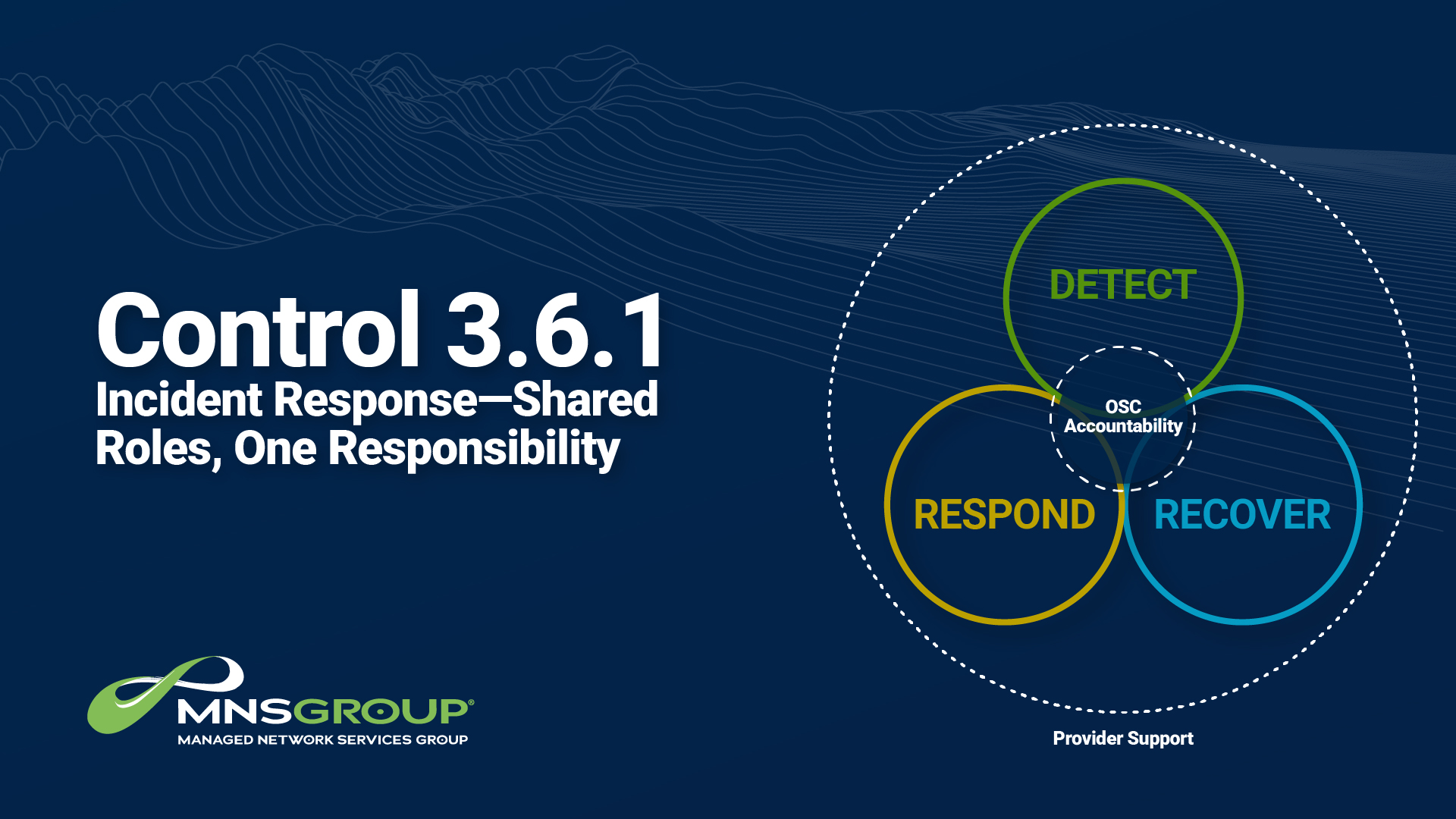

This control has nuance because it sits squarely between technical response (often handled by service providers) and organizational accountability (which belongs to the OSC).

What the C3PAO Looks For

During an assessment, we’re looking for clear evidence that:

- Your organization has an incident response plan that includes roles, responsibilities, and procedures.

- Those roles include both internal staff and any external providers that support detection or containment.

- Employees know how to report an incident and to whom.

- You’ve practiced or reviewed your response plan periodically.

- The OSC retains ownership of reporting, coordination, and post-incident review.

A well-written plan is not enough. The C3PAO will want to see that your organization has tested or used it — even if just through tabletop exercises.

Where Shared Responsibility Can Break Down

Many organizations assume their MSP or SOC provider “handles incidents.” That’s partly true — your provider may detect, isolate, or mitigate technical issues.

But that’s not the same as incident handling.

An MSP can alert and assist. But only the OSC can:

- Declare an event as an official incident.

- Decide when and how to escalate or report it.

- Notify customers, the DoD, or law enforcement if required.

- Document the lessons learned and implement changes.

In other words, your provider can help stop the fire — but you decide whether to call the fire department.

If your Shared Responsibility Matrix (SRM) doesn’t clearly define those lines, it’s a gap waiting to show up in an assessment.

The Leadership Imperative

Incident response is a leadership process. It requires decision-making authority, communication clarity, and accountability.

Here’s what strong incident handling looks like:

- A written plan that names roles, escalation paths, and communication steps.

- Providers’ responsibilities aligned with your internal chain of command.

- A process for documenting and reporting incidents and corrective actions.

- Periodic testing and updates to ensure the plan still fits your organization’s structure.

Leaders should ensure that when an incident occurs, no one says, “Who’s supposed to handle this?”

A good response plan prevents confusion. A great one prevents chaos.

Why It Matters

CMMC and NIST frameworks treat incident response as both a security and a maturity indicator. A well-run incident response process shows that your organization understands its environment, communicates effectively with partners, and can respond decisively to protect Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI).

Incidents don’t define compliance failures — unmanaged incidents do.

So as you prepare for assessment, ensure your plan reflects how you’ll actually operate during an event — and make sure your providers know their roles just as clearly as your employees do.

Because when something goes wrong (and eventually, it will), your success depends on whether your plan becomes a checklist or a lifeline.